Chinese Canadians of Yahk

- Greg Nesteroff

- May 8, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jul 7, 2025

In her 1983 book, The Unforgotten Memories of Yahk, the late Rita Dickson mentioned several Chinese-Canadian-owned businesses in the community, including a restaurant and laundry destroyed in a March 1924 fire. She said sometime thereafter, Lem Chong operated a restaurant, which in turn burned down in 1928. The book also includes an undated photo of a Chinese restaurant next to the government liquor store, but there is no indication what it was called or who ran it.

Further, Dickson wrote that at the local sawmill site, the CPR built about 20 homes for workers and their families, “and at the east end a few more were built for the Chinese people.” Chinese gardens are depicted in two photos near the lumber yard.

Aside from Lem Chong, no Chinese Canadians are named in the book and none are depicted. That’s no fault of Dickson’s, since none remained in Yahk by the time she arrived there in 1955. She relied on the memories and photographs of others. But thanks to new online tools, we can get a better picture of Yahk’s Chinese Canadians, figuratively and literally.

The sawmill in Yahk, seen here in 1919 or 1920, employed Chinese Canadians. (MSC130-3644 courtesy of the British Columbia Postcards Collection, a digital initiative of Simon Fraser University Library)

In 2023, Library and Archives Canada released a huge collection of immigration documents, created as part of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 (otherwise known as the Chinese Exclusion Act), which virtually stopped Chinese immigration to Canada until 1947.

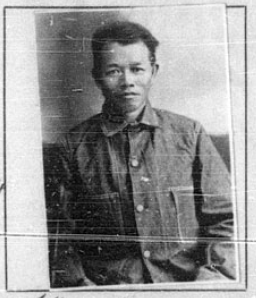

This paper trail was part of an ongoing and practically obsessive effort by the federal government to monitor Chinese residents. As a side effect, everyone was photographed, and in many cases, the photos affixed to those certificates and documents are the only ones known to survive of each person.

It’s possible to search the Library and Archives Canada database by keyword/place name, and thus, we can generate a list of 10 Chinese-Canadian men who lived in Yahk in 1924 and see what they looked like.

Wo Man, 36, was proprietor of the BC Cafe, which had been around since about 1920. His certificate was processed the same month as the above-mentioned 1924 fire that destroyed his business. He had been in BC since 1906 and was exempted from the head tax.

Allen Mar alerted me to other immigration certificates issued whenever a Chinese person travelled out of Canada. These reveal Wo Man was actually Wong Wo Man (based on his signature). As of 1920, he lived in Cranbrook. After being burned out in Yahk, he went to Kimberley where he worked at the Yale Cafe as of 1928. He left Canada twice more, each time while still living in Kimberley. The last certificate showed him as age 61 and about to go from Vancouver to Hong Kong via San Francisco. However, the certificate was stamped as cancelled.

Lee Kee King, 30, was a cook, although it’s not clear if he worked in the restaurant. He came to BC in 1908 and left a wife in China. He’d paid a $500 head tax, which, unusually, was refunded, although the certificate didn’t explain why. It could be that he’d entered Canada as a student, which would have qualified him for an exemption, and officials realized the mistake, or he requested the refund after learning he was supposed to be exempt. His photo showed him to be a dapper young man in a bow-tie.

Mah Yuig Yuey, 24, ran the laundry. He’d been in BC since 1914. He too had paid the $500 head tax and had a wife in China.

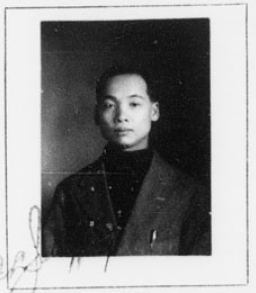

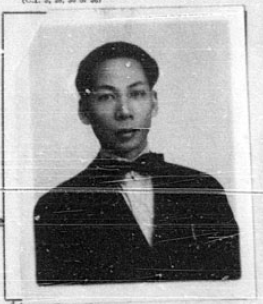

Wo Man, Lee Kee King, Mah Yuig Yuey

The remaining seven men all worked at the local sawmill. I’ve summarized their particulars in the chart below. They ranged in age from 21 to 51. All had paid a head tax, and all but one (Lee Hong Kam) had a wife in China. One of them (Lee You Nuey) had apparently come to Canada at age 13.

Name | Age | Arrival in Canada |

Quan Yue Boo | 37 | 1912 |

Jew Chu | 49 | 1903 |

Lee Chuey (Kim Lee) | 51 | 1900 |

Lum Kan Dai | 35 | 1910 |

Dar Man Dong (Dere Moon Ong) | 24 | 1918 |

Lee Hong Kam | 21 | 1919 |

Lee You Nuey | 21 | 1913 |

I haven’t had any luck finding out what became of these men, except one. At the bottom of Lee Hong Kam’s immigration form is a handwritten notation indicating he returned to Canada in June 1952 on a passport, then departed for China in January 1953 to get married. By that time he would have been about 50.

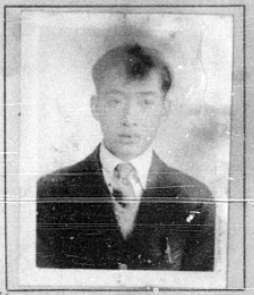

Dar Man Dong, Lee Chuey, Lee You Nuey

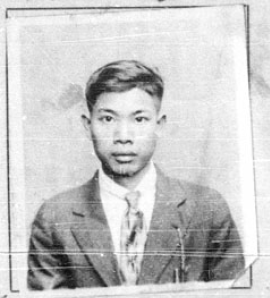

Clockwise from top left: Lee Hong Kam, Jew Chu, Lum Kan Dai, Quan Yue Boo

Also helpful for identifying Chinese Canadians are census returns, which provide us with names, but no photos. None were listed in Yahk on the 1911 census (although a couple worked as railway cooks at nearby Ryan).

On the 1921 census, we see 13 men working as labourers at the Yahk sawmill (which also employed half a dozen Indo-Canadians). They are listed below. All were married.

Name | Age | Arrival in Canada |

Chan Gah | 22 | 1918 |

Lee Long | 20 | 1911 |

Wong Hong | 36 | 1904 |

Wone Sing | 41 | 1913 |

Chow Chew | 46 | 1903 |

Der York | 54 | 1899 |

Wong Lee | 53 | 1900 |

Hong Yuen | 50 | 1899 |

Wong Sue | 40 | 1899 |

Lee Sam | 33 | 1913 |

Chew Kong | 51 | 1898 |

Lee Fong | 54 | 1891 |

Loy Kee | 42 | 1903 |

Three other men, listed below, cooked at the sawmill. Only Sam Chew was married.

Name | Age | Arrival in Canada |

Lee Yuen Hou | 18 | 1913 |

Allen Kee Lee | 20 | 1909 |

Sam Chew | 37 | 1909 |

Lee Yuen Hou was presumably the same man as Lee You Nuey/Huey, for whom there is a 1924 immigration certificate.

The 1921 census also shows three men running a restaurant at Yahk: proprietor Toy Low, 45, who came to Canada in 1894; and waiters Tong Wong, 24, who arrived in 1918; and Yick Wong, 23, who arrived in 1912.

That brought the total Chinese population in 1921 at Yahk to 19, all male.

One of the sawmill workers on the census, Chan Gah, also known as Chen Gar or Chan Gar, met a sad fate. On Oct. 13, 1921, he spent the afternoon fishing from a raft on the Moyie River, about three miles east of Yahk. Early that evening, a friend who was about 100 yards away on the riverbank noticed Gar’s feet floating on the water. He had presumably fallen off the raft.

The friend, who was unidentified in a story published in the Nelson Daily News, went to Yahk to notify the police. A search began early the next morning, and Cst. W.H. Laird found the body. A funeral in Cranbrook was “attended by a number of friends” from Yahk. Gar’s grave is unmarked. His death registration indicated he was 30, but the census conducted earlier that year said he was 22.

No other Chinese deaths were ever recorded at Yahk.

• Only two Chinese Canadians were listed on the 1931 census at Yahk (even though we know others lived there at the time). Neither had been there seven years earlier when the Exclusion Act documents were created. They were Wong Fonk Quong, 39, and Wong Kim, 60, both railway cooks. The former was single and came to Canada in 1921. The latter was married and had been in Canada since 1892.

• At least four other Chinese-Canadian men lived in Yahk in the 1920s and ‘30s.

In September 1924, Lim Now was convicted of opium possession and given the choice of a $200 fine or six months in jail. Unable to pay, he was admitted to the provincial jail in Nelson, along with Ching Toy of Cranbrook, who was convicted of the same charge and received the same sentence.

• According to a note in the Cranbrook Herald of June 4, 1925, Lee Dye ran the Depot Cafe in Yahk, but he sold it that month to a Mr. Hall, who also owned the Yahk laundry. Lee Dye then established the Century Cafe in Cranbrook, in partnership with Tong Sim.

• For the most part, Chinese Canadians weren’t included in Yahk’s civic directories, but I found some exceptions: from 1926-31, the Mah brothers were listed as running a restaurant, although their first names weren’t given. Nor was the name of the restaurant. From 1934-43, Charles Mah Ming was listed as a restaurateur on his own. We might presume he was one of the brothers. Either way, he appears to have lived at Yahk longer than any other Chinese Canadian.

He was mentioned in the Yahk notes published in the Nelson Daily News on Oct. 21, 1937: “Mah Ming, who, for many years, conducted a restaurant business here, has returned after a lengthy visit in Hong Kong.” And again on Sept. 5, 1938: “Charlie Mah Ming, proprietor of a local cafe, left Monday to visit relatives at Hong Kong.”

From 1929-32, Chong Lim was also shown in the directories as running a restaurant. He is presumably the same man as Lem Chong, mentioned in Rita Dickson’s book as having been burned out in 1928. He must have found another location.

While it’s no small thing to add names and some faces to these men, I wish we knew more about their individual stories.

— With thanks to Allen Mar

Updated May 13, 2025 to add more about Wong Wo Man and Lee Kee King. Updated on July 7, 2025 to add a note about the homes and gardens at the sawmill.

Thanks, Greg - one can only imagine what these men's lives were like. I'm glad you've acknowledged them.

Doreen