New Denver’s cemetery story

- Greg Nesteroff

- Jan 22, 2019

- 14 min read

Updated: Jan 11

Despite being such an historic and picturesque site, little has been written about the history of New Denver’s cemetery — until now. This story originally appeared in the Winter 2019 edition of The Silver Standard, the newsletter of the Silvery Slocan Historical Society.

The Silvery Slocan Historical Society hosted a well-attended tour of the New Denver cemetery in October 2018. (Paula Cravens photo)

In the upper, lower, and Masonic sections lie the remains of nearly 1,000 people, including many early pioneers of New Denver, Silverton, Sandon, and area.

The upper cemetery dates to 1892 and the death of pioneer prospector Jack Evans, who reportedly came to the area via the Arrow Lakes around 1886 with Capt. Robert Sanderson and a German man whose name is unknown. They prospected up to what is now Seaton Creek looking for gold. Although they found galena float, they didn’t consider it valuable, and left the area. [1]

Nothing is known about Evans’ background, although his surname was reputedly actually Evanson. [2] He returned to the area following the start of the Silvery Slocan mining rush in the fall of 1891 and made his home at Nakusp. He was said to be a “strong traveller in the mountains, packing 100 pound packs and never seeming to tire.” [3]

He was “liked by everyone who knew him. Of a quiet, retiring disposition, he was not often seen in town, preferring to be on the mountains following his profession.” [4]

On a visit to New Denver, he was stricken with appendicitis. But there was no doctor in the camp. He was taken to a cabin and plied with whatever patent medicines could be found. He rapidly grew worse. At one point he rose from his bed, looked at the sunset, drank some water, and lay down again. His final words were: “It’s getting dark.” [5]

Evans died on Oct. 14, 1892. The next day, a cemetery site was chosen a little ways from town. Pioneer newspaper publisher Robert T. Lowery was not there, but later recorded the scene: “Red Paddy dug the grave and Mexican Bill delivered a burial service from memory. There was not a dry eye at the funeral, and that night there wasn’t but one sober man in the camp, and it was only through a weakness in the whisky that funerals did not become epidemic until the grief over Jack’s death had died away.” [6]

Nelson Miner editor David Bogle began collecting donations to mark Evans’ grave, as a measure of “respect for one of the best men in the country … Jack Evans was one of the oldest and most respected citizens of the interior. He died as he had lived, far from the boundaries of civilization and has left no monument to his memory save the record of hard work and faithful service. may we all make as good an ending.” [7]

The collection reached $23.50 with the largest donations of $5 each coming from S.H. Seroy and J.F. Hume & Co. [8] The Miner doubted this would be enough to buy a headstone and ship it to New Denver, but felt hamstrung by not having anyone in the Slocan to solicit donations. [9]

By the spring of 1893, his “old partners and friends” were scolded by the Nelson Tribune for allowing his grave to become neglected, but it was thought the sale of a mining property that belonged to his estate would raise enough money for a headstone. [10] So Bogle turned over the donations to the Kootenay Lake Hospital Society. [11]

The second burial in the cemetery was that of Mrs. Thorburn, the mother of Silverton hotelier Grant Thorburn, who died on May 5, 1893 at the head of Slocan Lake, age 72. [12] Her grave does not appear to have been marked either.

The third burial was likely Thomas Kirkland, a prospector from Ontario who died at the Bolander House hotel in New Denver on Dec. 7, 1893 in what the Nakusp Ledge described a week later as “brain fever.” He was about 48 and single.

According to the Nelson Tribune of Dec. 23, his neighbours “became alarmed” at his condition and moved him from his cabin to the hotel, where he “received all the attention possible in a town where there is no doctor.”

However, the next day he took a turn for the worse and died at 10 p.m. that evening. The Tribune correspondent described him as an “old-timer on the main line of the Canadian Pacific through the mountains.”

The fourth burial was Walter Hunt, killed in an accident at the Mountain Chief mine on June 26, 1894. A landslide swept him down almost to Carpenter Creek. His body was crushed almost beyond recognition. He had been a foreman for George Hughes on railway construction prior to coming to BC. In New Denver, he was a foreman for Hughes at one of his corrals and stables. He had only worked at the mine a short time. He left a wife and four children in Seattle. [13]

These fences denote some of the earliest graves in the cemetery, but only one has a grave marker within it.

This was followed by Mrs. Reed, the wife of Al Reed, who died at Silverton on July 8, 1894. They had only been married for three months. [14] Her place of burial was not stated, but it was probably New Denver.

Likewise Catherine Breeden (or Breedon), who died in November 1894, although the exact date was variously given as the 15th or 17th, and the place as Three Forks, Sandon, or Nelson. According to her death registration, she was 55, born in Missouri, and died of heart disease after three weeks. She left a son and daughter, Mrs. John Maxwell, who lived in New Denver. [15]

When Allan (or Allen) McPhee died on April 2, 1895, The Ledge stated that “Grave No. 7 has been filled in at the New Denver cemetery.” [16] McPhee was described as “one of the best known characters in the country.”

McPhee complained of chest pains before going to bed at Robert Cumming’s hotel in Sandon. A message was sent to the doctor at Three Forks, but before he could arrive, McPhee had died in agony of what was officially described as neuralgia of the heart. His body was sent to New Denver by train and interred before “a large turnout of friends from the surrounding camps.” [17]

McPhee was a New Brunswick native. He was either 48, 56, or 68, depending on conflicting accounts, and single. At one time he ran the ferry at Sproat’s Landing (near present-day Castlegar) and owned interests in several mining claims, including a promising property on Ten Mile Creek. He also did logging and sawmilling. [18]

(For more on McPhee and the geographic names he left behind, see Jon Kalmakov’s website.)

Burial No. 8 was Fred Butler of Three Forks, who on June 15, 1895 fell dead on the trail leading from his cabin. He was 37 or 38 and had been ailing for some time. Three years earlier he strained his left side. Later a growth appeared just below his heart. A subscription list was taken up and $125 raised to send him east for treatment. He was to have left the day he died. [19]

Following a coroner’s inquest, friends made a coffin and decorated it with blue velvet and flowers. His remains were taken to New Denver by push car, where C.E. Smitheringale conducted the funeral service according to the rites of the Church of England. Butler was known to have been packing on the Nakusp trail two years earlier. He came from Ottawa, where his cousin was police chief. [20]

On. Oct. 22, 1895, Otto Austin died at Sloan’s Hotel in Three Forks of “mountain fever.” He was either 23 or 25 and a native of Oshkosh, Wisc. [21]

Nine days later, Three Forks baker J. Wood spotted what he thought was a prospector’s pack in a creek. Grasping it, he was surprised to find a man’s body, the face disfigured. It was taken to the Slocan Star ore house, where a coroner’s inquest began. In the man’s coat pockets were found a Kaslo newspaper dated Aug. 1 and a bottle of whisky. The jury gave a verdict of death of unknown causes. The unidentified remains were buried in New Denver. [22]

The next several burials included:

• Mrs. Michael, who passed away at the Alamo concentrator on Nov. 28, 1895 after a six-week illness. The funeral procession was “perhaps the largest … ever witnessed in the district.” [23]

• Charles Drouin, or Dronin, a prospector who died on Jan. 19, 1896, age 48, after being brought to hospital in New Denver suffering from acute pneumonia. [24]

• Henry Smith, who died on Jan. 31, 1896, also from acute pneumonia. he was brought to hospital in new Denver from Sandon, having been badly injured in a fall from a ladder. He was also suffering from inflamed lungs. [25]

• Mary Kelly McInnes, who died at Sandon on Feb. 18, 1896 after a two-week illness. She was survived by her husband Neil, to whom she had been married a little over a year, and a baby daughter. [26]

If any of the 14 graves listed above were marked, they are no longer. The oldest marked grave (pictured) belongs to Henry James Sheran, son of Harry and Elvira May Sheran, who died on Aug. 31, 1896, aged six months and 14 days. [27] Harry was proprietor of the Sheran hotel, built in 1893, and a co-owner of the Molly Hughes mine.

The second-oldest surviving marker belongs to Ellen Lovatt, who died at Sandon on Jan. 18, 1898, age 61, of pneumonia with bronchial complications. Her husband was lumberman George Lovatt, who went on to serve as Sandon’s mayor. [28] Lovatt’s grave is the only one among several within picket fences in the cemetery’s oldest section.

Only a few wooden gravemarkers remain in the cemetery, most unreadable. One belongs to Elizabeth Chambers, who died in 1908. It has deteriorated markedly in the last 20 years.

The village repainted some other wooden markers in the 1980s and returned them, but six have since been removed again for safekeeping. They include one that belongs to John Madden, infant son of John and Mary Madden, who was born in March 1895 and died in August 1896.

There’s also the marker of William Callahan, a miner at the Payne mine, who died of pneumonia in 1899. His headboard was the only one in the cemetery that said “W.F. of M” on it – Western Federation of Miners.

And there are the markers of two miners, Antonio Bogattin and Joseph Digiovoni, who died in an avalanche in the Alamo basin in 1900; plus Nellie Dewar, who died at Three Forks in 1902, age three, and Robena Mowat, who died in New Denver in 1901, age 58.

Wooden gravemarkers removed for safekeepking include those of John Madden (d. 1896), Antonio Bogattin (d. 1900), Nellie Dewar (d. 1902), and William Callahan (d. 1899).

Governance and maintenance of the cemetery appears to have been haphazard to non-existent until 1901, when Rev. A.E. Roberts headed a citizens committee to “survey, fence and otherwise protect and beautify” the cemetery grounds. The idea had reportedly long been discussed, but nothing had ever been done. It was estimated that $150 was needed to put things in proper shape. Charles Sandiford was tapped to survey the grounds, plot the lots, and mark the avenues. He was not a registered surveyor, but rather the son of the Bosun mine’s manager. [29]

The collection raised $67.50, including $15 from the Silverton Miners’ Union and $25 from the New Denver Miners’ Union. Part of the cemetery was to be set aside for the exclusive use of the latter, but if this actually happened, we don’t know which section was theirs. [30]

The final mention of the project noted completion of the cemetery survey was expected within a week, to be followed by construction of the fence. But whether any of it actually happened is unknown. [31]

On April 3, 1906, a deed was finally registered in the name of the New Denver Cemetery trustees, comprised of Block 83 of Lot 550, at the northernmost end of the McGillivray Addition to New Denver. Block 82 was added sometime later. The trustees were: Jacob Brouse, Angus McInnes, Amos Thompson, Charles Adasy, Edward Angrignon, Herman Clever, and Charles Rashdahl. [32] Some were eventually buried there.

In 1930, the trustees turned over maintenance for the cemetery to the recently-incorporated Village of New Denver. [33] In 1940, although the cemetery was far from full, the village applied for and received approval to add Blocks 73 and 74 of Lot 549, which today is the lower, or new cemetery. [34]

A new cemetery board was also appointed at that time: A.D. Trickett, William Jeffery, Andy Jacobsen, and James Draper, with Trickett as chair. Draper was the local funeral director. [35] By 1965, all four men had died, none having ever been replaced as trustees. Finally a new (and seemingly final) board was appointed: Clifford Uphill, John Huntley, Senya Mori, and Frederic Angrignon. [36]

An order-in-council adopted in the latter year transferred ownership of the old cemetery from the trustees to the village, [37] which then adopted a new cemetery bylaw. [38]

Burials are still taking place in reserved plots in the upper cemetery, but new plots are not being sold. The easternmost 100 yards are reserved for Masonic use, where the earliest burial is from 1941. The village took over maintenance of this section in 1968. [39] Why are these graves so far away from the rest? The answer lies in Masonic funeral rites: they are as far east as possible.

G. Parker drew cemetery plans in 1979 and 1980. Based on them, the Regional District of Central Kootenay compiled a cemetery map in October 1988 that is still in use.

In 1943, during the Japanese-Canadian internment, a crematorium was built at the lower cemetery in 1943 by the E.W. Somers funeral home of Nelson to handle the remains of the large percentage of Nikkei residents who were Buddhists. It was at that time the only crematorium in the interior. It operated until 1967 and then the equipment was dismantled. [40] The building stood until just a few years ago when it was viewed as a safety hazard and torn down.

Of the more than 240 Japanese-Canadians who have died at New Denver since the start of the internment in 1942, only 24 are known to have been buried there. There are two marked graves in the upper cemetery, plus 17 in the lower cemetery, most in the southwestern section, as well as five unmarked graves.

There is also a veterans section in the lower cemetery. Some military burials can be found in the upper cemetery, but just a handful.

An unofficial Italian section is at the south end of the upper cemetery, including a combined marker (pictured) for six miners who died over two weeks in January 1919 of Spanish flu: Joseph Cervo, Giuseppe Losco, Leopoldo Lissa, John Barbaro, Ulisse Stedile, and Joseph Cechelero. They ranged in age from 28 to 42. In Stedile’s case, his wife and children in Italy never learned he was dead. Only many years later did his family find out what happened. [41]

One group not represented in the cemetery is the Doukhobors, for whom there are few if any burials. This is partly explained by the fact that a Doukhobor cemetery exists at Hills.

Today findagrave.com lists 972 burials in the upper and lower cemeteries combined.

UPDATE: In 2023, I noticed that a photo in the Lovatt family fonds at the BC Archives was described as a “B&W copy print of the grave of Ellen Lovatt, in New Denver,” circa 1899, although the image was not available online.

In January 2026, I thought it might be worth taking a flyer on a scan. And I’m so glad I did. When I received the image a few days later, I was floored.

At the very least, I expected the photo would show the stone Lovatt grave marker (which is still there) when it was new. But I hoped it might also show other graves in the background. And boy, does it ever! I count 11 total, as well as what appears to be a fence marking the cemetery’s west boundary.

Only the Lovatt grave still has a marker on it today, but some of the other fences depicted also remain, though they are mostly fallen over. It may now be possible to identify who a few of them belong to. In other cases, we’ll at least be able to approximate where the graves are, even if there is nothing at all to mark them.

(Image F-09964 courtesy Royal BC Museum and Archives)

The same view today. Several huge trees have since grown, including one within the fence of Ellen Lovatt’s grave.

Other observations about this remarkable photo:

• Nine of the 11 graves shown have visible markers, but only five are readable in whole or in part. Ellen Lovatt’s appears to be the only one that is not wooden.

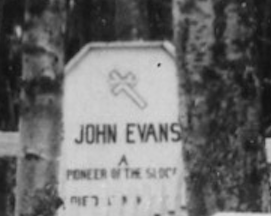

• While I had presumed that Jack Evans’ grave, the first in the cemetery, was never marked because the fundraiser for that purpose fell short, this photo shows that it did in fact have one! It reads in part “John Evans/A pioneer of the Slocan.”

• The grave to the right of Evans’ looks could be Albert Stirrett’s. All I can see is “A. H — rett.” (I don’t know of any other early burials ending in “rett.”) If so, that would confirm the photo was taken in 1899 or later, since Stirett died in December 1898.

• W.H. (Billy) Smith’s marker bears the following epitaph, which apparently was quite popular at the time: “’Tis hard to break the tender cord/When love has bound our hearts/’Tis hard, so hard to speak the words/Must we forever part.” The authorship is unknown. The longer version is here.

• The marker to the left of Billy Smith’s says “William,” who was perhaps the son of a “Mr. and Mrs. J.” something. The possibilities are William Walton, William J. Lade, William Darlington, and William McLeod. I think Lade is most likely because it looks like the marker has a middle initial. However, there are a couple of shovels and some rope on the fence. Does this indicate a recent burial? If so, it wouldn’t be Lade's, because he died in late February 1898 and presumably there would still be snow.

• The burial at far left, top, has a footboard that appears to say W A H or W A N. Doesn’t match any initials I have on my list.

• Not only is this the earliest photo of the cemetery, it’s one of very few photos of any West Kootenay cemetery from the turn of the 20th century.

NOTES

1. The Ledge (New Denver), Nov. 5, 1896

2. The Miner (Nelson), Oct. 29, 1892

3. The Valhalla Mountains, Innes Cooper, 1996

4. Kootenay Star (Revelstoke), Oct. 22, 1892

5. “Death of Jack Evans,” The Week (Vancouver), R.T. Lowery, June 8, 1907

6. Ibid. Another version of the story, in Clara Graham’s Kootenay Mosaic (1971), p. 10-12, states that Evans fell ill near the lower end of Slocan Lake. Ike Lougheed and others rowed him halfway to New Denver when a storm drove their boat to the west side of the lake, where they were forced to remain for a day (now known as Evans Creek). Evans died there and Lougheed and another man picked a place for his grave in New Denver.

7. The Miner, Oct. 29, 1892

8. The Miner, Nov. 5 and 12, 1892

9. “Jack Evans’ memorial,” The Miner, Dec. 31, 1892

10. The Tribune (Nelson), May 11 and 18, 1893

11. “Will turn the money over to the hospital,” The Tribune, June 1, 1893

12. The Tribune, May 11, 1893

13. “Killed at the Mountain Chief mine,” The Tribune, June 30, 1894

14. The Miner, July 14, 1894

15. Slocan Times, Nov. 17, 1894, Nakusp Ledge, Nov. 22, 1894 and death registration for Catherine Breedon, BC Archives Reg. No. 1894-09-9001777, Microfilm B13358

16. The Ledge, April 4, 1895

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid., Slocan Prospector, April 11, 1895, and death registration for Allen McPhee, BC Archives Reg. No. 1895-09-900219, Microfilm B13358

19. The Prospector, June 20, 1895 and The Ledge, June 20, 1895

20. Ibid.

21. The Ledge, Oct. 24, 1895

22. The Ledge, Nov. 7, 1895

23. The Ledge, Dec. 5, 1895

24. The Ledge, Jan. 9 and 16, 1896 and death registration for Charles Dronin, BC Archives Reg. No. 1896-09-62794, Microfilm B13104

25. The Ledge, Jan. 6 and Feb. 6, 1896 and death registration for Henry Smith, BC Archives Reg. No. 1896-09-162834, Microfilm B13104

26. The Ledge, Feb. 20, 1896 and The Miner, Feb. 29, 1896

27. The Ledge, Sept. 3, 1896

28. Mining Review, Jan. 22, 1898

29. “To fence the cemetery,” The Ledge, June 20, 1901

30. “For cemetery improvements,” The Ledge, June 27, 1901 and The Ledge, July 4, 1901

31. Ibid.

32. BC Order-in-Council 11, approved Jan. 7, 1965

33. Village of New Denver, Cemetery Bylaw No. 7, adopted May 7, 1930

34. BC Order-in-Council 1422, approved Oct. 29, 1940

35. BC Order-in-Council 1686, approved Dec. 20, 1940

36. BC Order-in-Council 11, approved Jan. 7, 1965

37. BC Order-in-Council 256, approved Feb. 3, 1965

38. Village of New Denver, Cemetery Bylaw No. 161, adopted Feb. 2, 1966

39. The Kootenaian (Kaslo), Nov. 28, 1968

40. “Interior now has a crematorium,” Arrow Lakes News, April 22, 1943 and Public Utilities Commission report 1969, viewed via Google Books

41. findagrave.com/memorial/165325566/ulisse-stedile/photo#view-photo=152424611, viewed Jan. 6, 2019

With thanks to Catherine Allaway, Paula Cravens, Pat Goulden, Chris Kölmel, Peter Smith, Henning von Krogh, and Bruce Woodbury

Directions to the lower (newer) section:

From Highway 6 in New Denver, proceed east on Highway 31A for about 0.8 km. Just prior to Denver Canyon Road, make a sharp right to the entrance (no signage). A rough track at the opposite corner from the entrance leads up to the older section.

Directions to the upper (older) section:

From Highway 6 in New Denver, proceed east on Highway 31A for about 1.5km. Turn right onto Denver Siding Road for about 120m, then continue on 10th Avenue/Atlantic Street for another 120m, where you may park at the corner and walk in.

Updated on Aug. 2, 2022 to add the photos and text that originally appeared in the newsletter and on Aug. 21, 2022 to add the death of Thomas Kirkland. Updated Jan. 11, 2026 to add the 1899 photo and discussion about it.

Hi Greg - it was great to read & understand more about the history of the New Denver cemetery. Hal Wright & I are currently working on a more in depth history of the Sandon cemetery. We thought that this may be of interest to you. April 8, 1901 a John Robertson Barr (reported as a suicide) the more I delve into this individual I’m convinced he was murdered. The way he died was quite brutal and doesn’t make sense. We did find out that in the April 13, 1901 the Mining Review Mr. Barr was interred in the New Denver cemetery.

We are curious if there is a historic plot map of the New Denver cemetery in the 1900 era?…

Great article as usual Greg. No. 3 might have been Thomas Kirkland. This would explain the "gap" before Allan McPhee see Nelson Tribune, 23 December 1893; The Ledge, 21 December 1893.

Yes! Become a member now, and we will email it to you.

Is the issue of The Silver Standard with the story about New Denver Cemetery still available? If I became a member of the Silvery Slocan Historical Society now, could I still get a copy?... my ancestors have 2 family plots in the old section (Clever & Carter). I am coming up in the summer to bring my Uncle’s ashes back home.