The Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling mill

- Greg Nesteroff

- Jul 13, 2021

- 19 min read

Updated: Nov 6, 2024

Summer 1981: An eight-year-old girl exploring the woods around Springer Creek Falls in Slocan comes across a set of concrete foundations. While the ruins betray no obvious sign of what once stood there, they set her imagination ablaze. They seem magical, as though evidence of a lost civilization.

While it feels like she has stumbled onto her own secret world, she is far from the first person to puzzle over this site. And once the Springer Creek campground expands in 2000 to add campsites immediately adjacent to the ruins, dozens or hundreds of visitors join each year in wondering about them. Asking locals might produce the correct answer. But it might just as easily produce a conflicting theory.

The actual origin of these ruins is a unique intersection of two key aspects of Slocan’s history: mining and the Japanese-Canadian internment.

For this was the site of the Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling Company’s mill, built in 1936. It began operating the following year to process ore from the nearby mine of the same name, but didn’t last long. In 1942, the mill, along with an ancillary building, was converted into housing for interned Japanese-Canadians.

Concrete ruins adjacent to the Springer Creek campground, as seen in 2020.

Summer 1935: William Randolph Green, a 26-year-old mining engineer, checks out the old workings of the Ottawa mine and thinks it might have some life in it yet.

The mine has mostly been dormant for the last 13 years, but was once among the chief producers in the Slocan City camp. Since 1896, it has shipped large amounts of silver and lesser amounts of gold, lead, zinc, and copper, together worth an estimated $750,000 (about $14.7 million today).

After going great guns for the first few years, the Ottawa was acquired by the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Co. and leased to a series of operators. In 1920-21, one such group, the Ottawa Mining and Milling Co., built a mill capable of processing 50 tons of ore per day, but it burned in 1922, possibly due to a carelessly discarded cigarette. The company then held a fire sale of its equipment, including a small aerial tramway, Pelton wheel, and crusher, the latter two of which were described as “slightly damaged.”

Randolph Green represents the Ottawa Silver Syndicate of Spokane, which leases 25 claims in the Ottawa group from CM&S with an option to buy. He and fellow engineer John J. Stanford are satisfied there is still literally tons of profitable ore to be mined and processed.

A new Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling Co. is formally incorporated in Washington state on the last day of 1935 with an office in the Sherwood Building in Spokane, and registered in BC the following April as an extra-provincial company.

Green serves as president, managing director, and mine manager. The rest of the initial board includes James J. Biggar, as vice-president and treasurer; and Gene Wilson Biggar, F.M. Chastek and George J. Reiling as directors. Charles H. Stolz is ex-officio secretary while Cecil R. Thomas is later named assistant secretary. All are from Spokane except Gene Biggar, who lives in Nelson.

The company is a family affair. James and Gene Biggar are Green’s stepfather and stepbrother respectively. Curiously, an L.H. Biggar was manager of the Ottawa in the early 1920s, yet he seems to have been no relation.

They begin selling shares (by mid-1936 there are said to be 350 stockholders, nearly all from Spokane and area) and announce plans to build a mill able to handle 100 to 125 tons per day, at a cost of $50,000 (nearly $1 million today). It will be designed so that capacity can be increased to 250 tons daily if need be. (The ad seen here is from the Spokesman Review of Jan. 26, 1936.)

The building will measure 175 feet long by 50 feet wide and will be electrified with a 120 horsepower diesel plant, although it is expected to be replaced eventually with a hydroelectric plant. An order is placed with the Union Iron Works of Spokane for flotation and ball mills, a crusher, and a filter press, among other equipment.

Unlike the earlier mill that burned, which was at the actual mine site in the hills about five kilometers northeast of Slocan, this one will stand just east of city limits, a little over one kilometre from downtown, on Parcel 1, Lot 2420 in the old Brandon townsite. (It’s not known who owned this property before, nor why this location was chosen, but it was along the road to the mine, close to Springer Creek, obviously vacant, and presumably available at a reasonable price.)

The A.H. Green company, one of Nelson’s leading contractors, is hired to build the mill and construction begins on May 13, 1936. The contract is said to be worth $10,000 ($200,000 today) rather than $50,000.

Are A.H. Green and Randolph Green related? They don’t appear to be, although when Randolph soon becomes the mine’s resident manager, he moves to Nelson and lives in the Terrace Apartments.

To the satisfaction of the company and its shareholders, silver prices increase and the workforce expands. Even before the mill begins operating, the company declares a dividend of a quarter cent per share.

Spokesman-Review, June 21, 1936

Spokesman-Review, Nov. 29, 1936

Spokesman-Review, Aug. 8, 1937

The fledgling mining company also makes a deal that is of great benefit to local residents: they invest in another 50 horsepower diesel generator to supplement their existing power plant and agree to provide the City of Slocan with electricity for its streets and homes.

Unlike neighbouring towns like New Denver, Sandon, and Nelson, which have enjoyed uninterrupted hydropower for 30 years or more, Slocan’s service has been spotty at best, and oftentimes nonexistent.

The mill building is completed in the fall of 1936 and “Ottawa Mining and Milling Company” is painted on the front. Despite its industrial purpose, its appearance is pleasing.

A correspondent for the Northwest Mining Review comments: “[H]oused in a building that glistened with a new coat of paint, the mill presents an attractive sight as you drive through the heavy wooded area at the mouth of Springer Creek.”

Ole Weiberg, a carpenter and stockholder, declares: “The mill is of A-1 lumber and well constructed.”

In addition to the mill, an assay office, machine shop and powerhouse are constructed nearby, along with large ore bins. However, the mill still needs more equipment before it can operate.

In January 1937, the company sends its first test shipment of five tons of ore to the Trail smelter, netting $872 (over $16,000 in today’s currency). It also exercises its option to buy the main Ottawa property from Consolidated Mining and Smelting, making payments of $15,000, $10,000, and $10,000 (about $280,000, $185,000 and $185,000 today).

The mill continues to sit idle over the winter. Tunneling at the mine continues, however, and additional shipments of ore are sent to the smelter. The company also acquires additional properties.

Stock certificate bearing the signatures of W.R. Green, president, and Charles H. Stolz, secretary, dated March 8, 1937 and held by W.R. Rathke. (Greg Nesteroff collection)

Reports about the mill’s imminent start-up repeatedly prove premature — it seems perpetually two weeks away. Various reasons for the delay are cited. Wiring not quite finished. Pipes need to be connected. Snow has to melt from the road to the mine.

But after some dry runs in May, the mill finally comes to life for real on July 10, 1937 under the watchful eye of operator Warren Antisdel, who has 20 years experience as a mill operator in the Coeur d’Alenes. In late September, it begins running around the clock. Eight men are employed in the mill, turning out 800 pounds of concentrate per day. Another 13 men work at the mine. The company appears to be hitting its metallurgical stride.

Also in September, lucky for us, the Department of Mines sends a photographer to capture the mill on film. Four of those photos, held by Library and Archives Canada, are seen below.

The Ottawa mill at centre and the powerhouse hidden in the trees at left. (Library and Archives Canada PA-15054)

(Library and Archives Canada PA-15023)

(Library and Archives Canada PA-15095)

(Library and Archives Canada PA-15202)

But then something goes wrong: Randolph Green is ousted as president. There is a dispute over his severance of $2,604 ($48,000 today). The other directors allege he “wrongfully converted the money to his own use,” but Green produces a signed settlement to the contrary. The board contends it erred in agreeing to the deal, as it was initially believed Green was owed money, but now it’s claimed to be the other way around.

A year and a half later, a trial is held before Washington superior court Judge Lon Johnson, who rules the evidence does not prove there was anything wrong with the settlement. Case dismissed.

Green goes on to work at mines in the Coeur d’Alenes and California, serves as assistant supervising engineer for the US bureau of mines in Spokane, then joins the Great Northern Railway as a geological development agent. (He is seen here in the Spokane Chronicle, Nov. 1, 1945.)

Back at the Ottawa mine, D.D. Fairbanks replaces Green as manager and Cecil Thomas takes over as president and general manager, but the mill is idled again over the winter of 1937-38. Although shipments to the Trail smelter continue, the mill does not resume operation until June 1938, this time under the direction of R.P. Handy of the R.S. Handy & Sons Metallurgical Works of Hillyard, Wash. By the end of the year, the mill is going flat out again, 24 hours, and the company says it plans to keep it going all winter.

Yet, while regular reports appear in Spokane and Vancouver newspapers about continuing shipments from the mine to the Trail smelter, the mill again sits idle.

A report in May 1939 suggests “a resumption of milling is expected in a few days,” but it doesn’t happen. In fact, the expensive and much-vaunted facility appears to have only operated for about nine months over three years. Its lack of use is not easily explained, for the mine continues to ship ore, although by the end of 1939, with silver prices nose-diving, it is leased to William Hicks. Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling continues to receive royalties on shipments.

By early 1942, the company goes into hibernation, although it will re-emerge after the war. But right now, the directors wonder what to do with the mill. The answer comes from a surprising source.

The Ottawa mill at Slocan, ca. 1936. The people are unidentified. The caption on the back reads: “Tom Gibson installed the diesels in the Ottawa Silver Mining Co.” (Evelyn Hurst/Slocan Valley Historical Society 2013-01-342)

Ottawa mill, ca. 1936. (Keith Purney/Slocan Valley Historical Society 2013-01-767)

Evelyn Gibson at the Ottawa mill, 1942. (Dorothy Gausdal/Slocan Valley Historical Society 2013-01-3119)

Ottawa mill, 1936. (Curtis family/Slocan Valley Historical Society 2013-01-1777)

July 1942: Japanese-Canadians are being interned in depressed West Kootenay mining communities, Slocan among them. The BC Security Commission, entrusted with the arrangements, leases a number of existing buildings in addition to constructing shacks on farmers’ fields to serve as crowded, makeshift housing.

Somehow the Ottawa mill comes to their attention, although it’s not clear who approaches whom. On May 23, 1942, the company signs a lease with the security commission for the duration of the war. The government will pay $50 a month ($800 today) for use of the mill, office, machine shop and powerhouse, all on District Lot 2420, as well as the 50 horsepower diesel engine and generator, which will be used to provide electricity to the Bay Farm and Popoff camps in addition to Slocan.

Signing on behalf of the company is Ed Graham of Slocan, now on the board and later to become the company’s Canadian manager and namesake of W.E. Graham school.

The mill’s equipment, presumably, is sold, although it’s not clear who buys it or where it goes.

Hirohito (Otto) Yanagisawa, 25, is the carpentry boss in charge of turning the mill into an apartment complex to house up to 100 people. The Vancouver Province observes: “Sound of construction, [the building] runs up the side of a hill in steps. Even the ore bins have been made into comfortable living quarters, each unit larger than a hotel room.”

Because the mill is a multi-storey building that steps down progressively from the hillside, it really does resemble an apartment complex. There’s an entrance at the bottom, an exterior stairway to the top, and an upper-storey rear entrance. The building’s bottom level is turned into a community bathhouse, with separate sides for men and women. A boiler room to heat the baths is added to the building.

The conversion requires blasting out the huge concrete bases where various machinery once stood. This is accomplished without breaking a single window, but Yanagisawa is too modest to take credit, insisting that it really belongs to camp superintendent Walter Hartley.

Hartley considers the electrification of Slocan one of his greatest triumphs. He finds the powerhouse with two complete 440-volt diesel units, both in “deplorable shape.”

But he learns of two young Japanese-Canadian men who hold masters’ tickets and another who is a marine engineer. All are familiar with diesel engines. They are tasked with repairs and do a “sweet job” of it, Hartley declares. He surveys a mile-and-a-half long 110-volt power line throughout the city and electrician Shaw Mizhuhara “boasts of the swell job” on the line and the wiring of homes.

Another building on site is also converted into housing. Residents later describe it as the bunkhouse or mess hall, but no such building is mentioned in the lease, so perhaps it is the former assay office or machine shop. (A Minister of Mines report refers to a “combined cook-house and bunk-house” that accommodated 25 men, but seems to suggest it was at the mine site.)

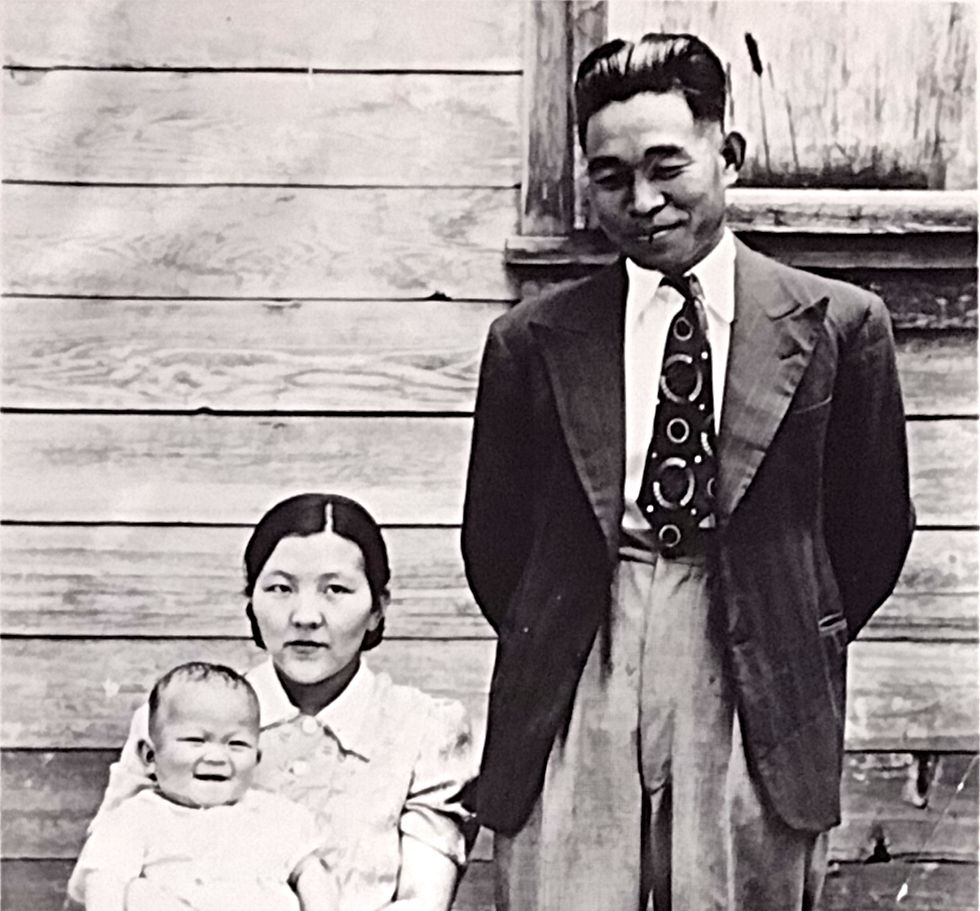

The mill’s apartments are intended for single people and smaller families. Among them are Babas, Inouyes, Fujinos, and Oikawas, plus a young couple, Isami (Harry) and Yoshiko (Ruth) Fukushima. Harry and his brother Tsutomu (Tom) work in the power plant, and are presumably the other two men who did the work Hartley was so impressed with. Harry is interviewed by the Vancouver Province in September 1942 for a propaganda piece relating how rosy things are in the internment camps.

The district is supplied with electric light from the dynamos of an old mining property, purchased [sic] by the commission. At the switchboard of a big Fairbanks Morse engine, producing 2,200 kilowatts, is Harry Fukushima.

Harry, formerly a fish broker, got his captain’s paper in 1937. He is an expert on engines of this type. One of Harry[’s] fishboats, the Brockton Point, has been taken over by the navy and is now being used in patrol work on the coast.

“I hated to leave the coast because the fishing business looks pretty good this year,” he said. “But I guess I am getting to like it here now.”

The powerhouse at the Ottawa mlll site, ca. 1944-46. The wood pile is fuel for the stove and the communal baths. (Courtesy Rosina Eto)

The so-called bunkhouse, a long and narrow building a few hundred yards from the mill, is divided in two for larger families. The Murakami/Eto family, formerly of the Fraser Valley, moves here from Sandon sometime after September 1944. Munekazu (Dexter) is about nine when he arrives with his parents, Tomio Murakami and Hisako Eto; younger siblings Sakue (Joyce), Yoshiko (Rosina), Mizue (Cherry), and Mamoru (Don); maternal grandmother Kikuyo, and aunt Shigeko.

“It’s crowded, that’s for sure,” Dexter says.

(Tom Murakami takes his wife’s surname, Eto, since she has no brothers to continue the family name, whereas Tom does have a brother. However, before this happens, the first three children are registered at birth under the name Murakami. They all later go by Eto, but the change is not made officially. Consequently, when Dexter enters the air force in 1953, he can’t be bothered to go through the red tape, and reverts to using Murakami. Rosina and Joyce also discover it is a hassle decades later when claiming their pensions.)

BC Security Commission record the Eto family was required to fill out in August 1942. Henry Nagai was Tomio (Eto) Murakami’s nephew while Hisako and Kikyuo were Shigeko’s sister and mother. (Courtesy Rosina Eto)

The family on the other side of the bunkhouse, the Sakamotos, has eight kids.

The Etos have two bedrooms, each with two double bunk beds. They have power; at least enough for lights, but no fridge. There’s a stove and a sink, but water has to be heated on the stove.

While Dexter considers the living arrangements a step down from their old house in Sandon, there are other benefits, for Slocan is a bigger community with more to see and do.

In all, Dexter guesses about 50 people live at the Ottawa site between the two buildings, including many seniors. There are perhaps a handful of other kids living in the mill apartments. The kids walk a short distance each day to Pine Crescent school in Bay Farm. Later, Bay Farm school closes and they attend public school in Slocan.

Pine Crescent School, Bay Farm, ca. 1944-46. Dexter Murakami is middle row, first from left. (Courtesy Rosina Eto)

Left: The Eto kids, in front of a trough that brought water to the internment camp at Bay Farm. Right: Don and Cherry Eto stand atop oil barrels at the Ottawa powerhouse. Both pictures ca. 1944-46. (Courtesy Rosina Eto)

•

The lease on the mill property says that while the security commission will pay the mining company rent, the company is on the hook for taxes. But the company makes no attempt to pay. By January 1945, the outstanding bill has reached $540 (over $8,300 today) and the deputy provincial collector in Kaslo writes to the government, asking that the lease payments be redirected toward the tax bill, using a provision in the Taxation Act.

It’s not known what, if any, action is taken. We do know that the lease is renewed on Oct. 29, 1945, covering the same buildings and diesel engine, plus the 120-horse power cylinder engine, which wasn’t explicitly mentioned in the previous lease.

July 10, 1946: Dexter returns home from fishing to discover he’s missed the afternoon’s excitement. At about 3:15 p.m., fire started in the powerhouse underneath a 750-gallon oil tank, which had been filled up only a few hours previously. The container ignited in seconds and flames shot upwards of 200 feet. The powerhouse, a single storey wooden structure, burned to its foundation. The machinery was, at minimum, severely damaged.

“I remember the men with hoses trying to save our house from burning, because we were so close,” Dexter’s sister Rosina later recalls. “All the people from Bay Farm and Slocan were up there watching it.”

Hoses attached to three hydrants were trained on the fire, and although unable to put it out for more than an hour, they did keep it from spreading to other nearby buildings, including the bunkhouse, 75 feet away. Several young men rolled barrels of oil away from the flames.

Harry Fukushima, who was on shift when the fire started, is unable to explain it. The fire marshal’s report points to a fuel spill as the probable cause. The government is held blameless.

News reports peg the loss at $15,000 ($230,000 today), but Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling estimates it at $9,000 ($138,000 in 2021), less scrap value of $1,500 ($23,000 now) and submits a claim for $7,500 ($115,000), pointing to a clause in the lease that requires the government to “leave premises in as good a state of repair as when first demised [leased].”

It’s not known what, if anything, is paid out. The last correspondence in the matter is from April 1947. Perhaps the outstanding tax bill is deducted from the claim, or they agree to call it even.

The power plant, at the time of its demise, was serving the surrounding internment camps, but it us unclear whether it was still serving the City of Slocan. As a replacement, the security commission brings in two gas engines and a generator and sets up a new powerhouse by combining two internment shacks moved from nearby Bay Farm.

It’s not known when the lease on the mill and surrounding buildings finally ends, but a letter of Sept. 7, 1946 suggests the government “will want to terminate the lease in … another month or so.” No pictures seem to survive of the renovated mill building itself during the internment era.

Afterward, the Murakami-Eto family moves into an old hotel in Slocan where things are less cramped. Then they rent the back half of a home on Main Street for $5 a month. Harry and Yoshiko Fukushima live in the front. Tom Murakami-Eto later adds another storey to his half of the house and his family takes over the whole building once the Fukushimas move to Toronto. The Sakamotos, whom the Etos shared the bunkhouse with, move to Revelstoke.

Left: Don Eto. Right: Rosina Eto. Both pictures may have been taken in front of the replacement powerhouse. (Courtesy Rosina Eto)

•

Two mysteries persist about the mill: why was it used so briefly after so much money was spent on it? And what happened to it?

As to the first question, it’s hard to know for sure because so much mining news was (and still is) relentlessly and unrealistically optimistic. Whatever obstacles cropped up, whatever gloomy assays emerged, were always portrayed to shareholders (and the world at large) as minor setbacks, certain to be overshadowed by the next glorious discovery.

The whole point of the mill was to reduce transportation costs by separating as much valuable ore from waste rock as possible before sending it to smelter, yet the company decided it made more sense to lease the property and not bother with the mill at all. Raw ore, rather than concentrate, went to the smelter.

“The Ottawa is bad,” said the late Bill Hicks, whose uncle Ted hauled ore for the mine in the 1930s, and whose namesake grandfather leased it in 1938 and kept it going for several years. “The vein is there, then it’s gone, and they had to find it again.” This pursuit was easier for a leaseholder, he explained, because they had lower overhead.

As to the second question, after the government lease expired, the buildings reverted to Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling, who clearly had no plans for them, especially now that all the equipment had been removed.

The mill was still standing as of 1953 when Dexter Murakami left Slocan, and when he returned to visit in 1957, the year his parents left town. But after that? It’s not clear. One account claims the mill “burned shortly after” it was built in 1937, but we know that’s not so. Maybe it did burn later on, although no one remembers such a fire. Perhaps it collapsed. Or more likely, it was finally salvaged for lumber or otherwise dismantled. In any case, the concrete foundations of the mill and office were left to the weeds.

February 2020: I notice Library and Archives Canada has two files on Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling, one to do with the company’s non-payment of property taxes when the mill site was leased to the BC Security Commission, the other with the fire that consumed the powerhouse.

I send away for both and soon receive a surprising response. It begins: “We need to inform you that the requested material has been informally reviewed … and was declared closed due to solicitor-client privilege. As a result, it cannot be released to the public.”

Solicitor-client privilege, 75 years after the fact!

However, the message adds, for $5 I can submit a formal access to information request, with the proviso that it may be denied. I do so. A month and a half later a notice arrives explaining Covid measures have delayed responses to such requests.

A few more months go by and I receive another message from a records analyst that begins: “The files in your request contain solicitor-client privilege information, so a lot of the content had to be redacted … We are consulting with the Department of Justice in order to assess the application of this exception in hopes of releasing more information. Unfortunately, this is a lengthy process and with the current delays and modified processes, I don’t have a specific time frame for you.”

However, the analyst offers to send the files with the redactions intact. I agree, and the results can be seen below. (I’m still waiting for the Department of Justice to weigh in.)

The files, which are best read from back to front, do contain a small amount of useful information, such as the terms of the lease, and the date of the fire, but the blacked-out sections prevent us from understanding how either issue was dealt with.

1945 and onward: The post-war corporate history of the Ottawa mine is complicated, as mine histories tend to be. For our purposes, it’s enough to say that the site is leased to many different operators who try to make a go of it, with varying degrees of success.

By 1951, Charles Stolz is the only remaining director from Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling’s founding. He organizes an adjunct company known as the New Ottawa Mining Co., while another sister company, Ottawa Uranium Mines Ltd., is founded in 1959 with an eye toward oil and gas development in Saskatchewan.

In 1962, Ottawa Silver Mining and Milling becomes Ottawa Silver Mines Ltd. and plans are announced for yet another mill. This one is built at the mine site and processes 75 tons of ore per day. It is in part-time operation by 1964, but doesn’t appear to last much longer than either of its predecessors.

Further name changes follow in 1965 (Slocan Ottawa Mines Ltd.) and 1972 (Slocan Development Corp.). The latter eases some of the stigma associated with Slocan Ottawa after stock promoter Morris Black is caught wash trading its shares (creating false impressions of market activity). In 1975, he’s jailed for six months and later fined for breaching the BC Securities Act.

Slocan Development, although relocated to Vancouver, continues to exist until at least 1994. It is latterly known as International Slocan Development Corporation.

Of the principals involved with the company’s early days, Randolph Green dies in Spokane in 1964, age 56. Charlie Stolz, a longtime realtor and mortgage broker (seen below in the Spokane Chronicle, Sept. 25, 1968), also dies there in 2000, age 92.

Otto Yanagisawa, who headed the effort to convert the mill into housing during the internment, marries Shizue (Sally) Obayashi in Slocan on Boxing Day 1942. They later settle in Nakusp, where Otto dies in 1992, age 74, following a career as a tugboat operator.

Only a few people remain from among the families who lived at the mill site.

Sadly, Tom Fukushima, one of the brothers who ran the power plant, falls from his trawler near West Vancouver in 1976 while shrimp fishing and drowns. He’s 61. The other brother, Harry, dies in 2000 in Toronto, age 86. Harry’s wife Ruth also dies there in 2013, age 95.

Dexter Murakami now lives in Salmon Arm while his sister Rosina is in Toronto. During a visit to Slocan sometime prior to 1973, Rosina was appalled to discover the old mill site had become an unofficial garbage dump.

The Ottawa mine itself, like many past producers in the Slocan, continues to be poked at. The last shipment of ore was in 1984, but prospecting and geochemical sampling occurred as recently as 2011.

1973 and onward: The new Highway 6, opened in 1973, passes through or very close to the now-deserted Ottawa mill site, but does not disturb its remaining concrete foundations.

On Sept. 17, 1978, Mayor Agda Winje cuts the ribbon on a picturesque campground, a little west of the mill site, officially known as Slocan Valley Lions Park, reflecting the work Earl St. Thomas and other member of the service club provided in creating it.

Among those present for the opening are Slocan Forest Products chief Ike Barber, MP Lyle Kristiansen, and the little girl we met at the beginning of this story, who happens to be the mayor’s granddaughter.

In the 1990s she will return to work here as the campground attendant. She also works at the visitor centre, built near the ball field in the mid-1980s and designed by local resident Minoru (Mitch) Nishimura in the style of one of the internment shacks that used to line Bay Farm, Popoff, and Lemon Creek. However, when a bus tour of former internees sees it, some are not impressed, for they feel it looks too good. The building is up to code and insulated, features that the originals did not enjoy.

The office/visitor centre in the Springer Creek campground, as seen in 2019.

Around 2000, the campground expands and the visitor centre is moved there to double as the office for what is now the Springer Creek RV Park and Campground. The campground and the mill site are all part of a peculiarly shaped 30.74 acre property, whose legal description is Lot A, Lot 2420. It is partly within village limits, but mostly outside, with a small satellite piece on the west side of Giffin Avenue. How and when did the village acquire this property? Not clear.

The expansion makes the concrete ruins of the Ottawa mill more accessible, and also opens up the question of what they were from. While many locals know the answer, confusion stems from the fact the Ottawa had three different mills in two different locations, and this one was several kilometers from the mine. Some think the foundations are the remains of a dam.

Today: The little girl-turned-campground attendant, whose name is Minette Winje, is now vice-president of the Slocan Valley Historical Society. She’s also my wife. Through the society we plan to create interpretive signage to finally explain the significance of these ruins. While much has been written about the Japanese-Canadian internment camps of the Slocan Valley, to my knowledge the fact the campground is adjacent to such a site has never been acknowledged. It might remove the aura of mystery, but the truth is more important.

The Ottawa mill site is seen in September 1937 (left) and from approximately the same spot in 2020. The faint outline of the old road can be seen in the foreground.

— With thanks to Rosina Eto, Dexter Murakami, Bob Barkley, Bill Hicks, and Minette Winje

Updated on Nov. 6, 2024 to add more details from the Vancouver Province of July 13, 1942 about the powerplant.

Hello! I'm a teacher in Langley and am collecting information about Japanese Canadians who were forcibly uprooted from the area during the war. If you would be able to pass along my contact information (Lkondo@sd35.bc.ca) to the Eto/Murakamis, I would be very appreciative! If they are willing to get in touch, I'd love to ask a couple questions. Thank you for the work you are doing in preserving these important stories!

We hope to see if it is possible to go underground and explore the mine.

I love the present-tense narration and the sleuthing - and the posts featuring your wife are always especially sweet. Looking forward to seeing your interpretive work onsite!